The uphill battle for subsidized housing in the GTA

Posted April 26, 2021 5:59 am.

Last Updated August 23, 2022 4:27 pm.

The search for subsidized housing can take well over a decade in parts of the GTA, leaving some residents vulnerable, including victims and survivors of domestic violence.

Filsan Abdi, a single mom to five kids, has been on the waiting list for housing in Peel Region since she was pregnant for the first time. That child, a son, is now 12 years old, and has four other siblings.

“I was in an abusive relationship,” said Abdi. “I applied for housing when I found out that I was pregnant with my first son, and since then I’m still waiting. My abusive relationship got worse, I had more kids, and I’m just stuck.”

The family of six all live in a cramped two bedroom apartment unit, which rents for $1,300 a month. Abdi doesn’t receive financial aid or support from the father of her children, who is currently in jail, and at times, struggles to make ends meet.

Filsan Abdi with her five kids. Photo credit: Filsan Abdi

In her initial application for housing back in 2009, she said she didn’t disclose that she was in an abusive relationship because she was scared.

“I was afraid if I stated I was in an abusive relationship, that they would call him and confront him, so he’ll know I said something,” she said. “I was so scared, because he made it clear that if I ever call the police and say I ever did anything to you, there was a big threat there.”

In 2018, Abdi said her then-partner was arrested and jailed for another crime. It was shortly after that she said she disclosed to the region that she had been in an abusive relationship.

In Ontario, the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing has stated that survivors of domestic violence may receive “priority placement for a social housing unit.”

Despite this, Abdi said she was told she didn’t qualify for priority status.

“They told me that he’s already in jail, so there’s no threat that you need it (housing) right now,” said Filsan.

CityNews asked Peel Region why Abdi and her family have been waiting for housing for over 12 years, the maximum wait time in the region. A spokesperson responded saying they could not comment on specific cases.

“There are certain factors that do impact an individual’s wait time for a subsidized housing unit including, but not limited to: location preference, building/site preference, and number of bedroom(s) requested,” wrote Stewart Lazarus, spokesperson for Region of Peel. “Unfortunately, units with three bedrooms or more are in exceptionally high demand, supply is extremely limited and turnover is very low. This impacts wait times even more.”

Abdi was told that she qualified for a three-bedroom unit because she has five kids, saying that’s the only preference listed on her application. Though she would prefer a three-bedroom townhouse for her family, she says, she is willing to move anywhere.

In addition to a 12-year-old, she has twin three-year old daughters and two boys aged seven and five. She said she regularly checks into her application status with the region and was told that she was at the top of the list for housing, but would just have to wait for space to open up.

“I didn’t ask for much, I just wanted anything,” she said. “I just wanted a place that if I lose my job or if I don’t work, that I don’t get evicted with my kids. That’s all I wanted.”

She shared a correspondence email with her area councillor, in which staff followed up with the Region of Peel’s subsidized housing team and were told her file is “eligible and awaiting housing offers.”

“Staff has also determined that your file does not fit either of the two priorities in the Peel Region which would expedite your case,” the email reads.

Housing gaps for victims and survivors

Abdi said her 13-year relationship often consisted of her being pushed, choked, threatened, and financially and emotionally abused.

She couldn’t talk about it with anyone, she didn’t know what her rights were, or what supports were available to her. Like many victims and survivors, housing and finances have been her biggest challenge.

“I just feel like I keep falling through the cracks and no one is noticing me,” Abdi said, no longer able to fight back tears. “I’m struggling to keep food on my table. I’ve been neglected by everybody, including the government. I just want my kids to have a proper home and I can’t give them that.”

Advocates have long called for service providers to be more flexible in their criteria for who is eligible for supports, including housing.

Nina Gorka, Director of Shelters, Girls and Family Programs at the YWCA Toronto, said Abdi’s experiences navigating the housing system aren’t unique, many other women have also faced the same difficulties.

“There has to be flexibility when we’re talking about housing and survivors of violence,” said Gorka. “It requires a multi-tiered, multi-invested solution when we talk about how do we solve the problem.”

Though there are options for women who experienced violence to access priority housing, Gorka said that comes with a number of challenges, including the criteria for eligibility.

“You would have to justify why you would be applying after you moved out. If you just escaped a violent home or had your life and the life of your kids jeopardized, you have to disclose your story,” Gorka said. “There are certain time constraints under which women have to apply in order to be qualified, and what we know is that some of the women who access services may not be ready to fill out lengthy application forms.”

Gorka explains that the applicants must either be deemed to be living in a high risk environment in that moment, or have left within a specific time frame (months), which would disqualify many people who require housing assistance.

Experts also add that just because a victim or survivor has left the abuser, it doesn’t mean that the threats of violence have stopped.

In instances where the abuser is living under the same roof, Gorka explains that part of the application would also require an individual to show “proof of the abuse” and have a third party backup the claim, something that can be difficult for survivors.

“Maybe they haven’t disclosed that abuse to someone, maybe they’re not on the lease, maybe they don’t have a relationship with the landlord,” Gorka said. “There’s a level of disclosure, and a level of assumption about which documents these women may or may not have, and sometimes that can be a barrier to accessing services.”

Wait times for housing

Across the Greater Toronto Area, tens of thousands of people are currently on the waiting list for subsidized housing.

As of March 31,2021, there are 79,322 households representing 148,012 people, currently on the waitlist for housing in Toronto. Families in search of a three-bedroom home have an estimated wait time of 13 years.

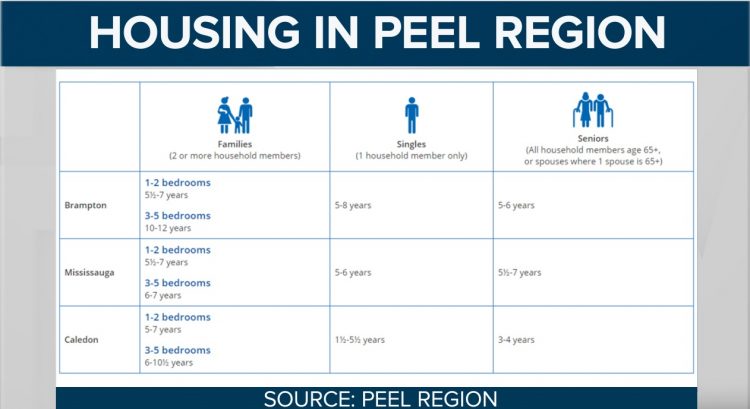

In 2020, there were 14,977 households on the wait list for subsidized housing in Peel Region. The wait times also depend on the location and the number of bedrooms required.

In Brampton, it can take between five-and-a-half to seven years to get into a one- or two-bedroom household, while those who need three- to five-bedrooms will have to wait twice as long.

Advocates and front line staff have raised concerns about the lack of affordable housing for women and children fleeing violence.

Some shelters and transitional homes are constantly filled to capacity and struggle making space for new people who require a bed, because their current clients are unable to secure housing.

Gorka says housing is the first basic necessity that anyone needs in order to begin rebuilding their life.

“What we’re seeing is people are staying longer and longer at our shelters,” Gorka says. “Shelters are meant to be temporary, they’re not meant to be a long-term solution, they’re not mean to be housing. It’s really hard to start working on anything else if you don’t have stability in your home.”

Gorka adds that there needs to be a multi-tiered approach to addressing violence against women and girls, with long-term investments in place to tackle poverty and injustices. Though this can be challenging, Gorka says it’s not an impossible solution, and all levels of governments needs to be involved.

“We have to have a national gender strategy, and a violence against women strategy,” Gorka says. “We have to have a national childcare policy, we have to look at maybe increasing minimum wage. We have to understand that there’s a ripple effect to all of this, and there’s a reason why we see cycles of violence continue.”

The ripple effect

Victims and survivors of family and intimate partner violence are oftentimes forced to navigate systems that advocates say come with barriers, which can then create ripple effects.

Abdi wants to bring her mother to Canada so that she can have a support system here at home. But the lack of adequate housing and income, has impacted that process.

“I tried to apply for a visa for my mom, and I couldn’t get it,” she explained. “My income isn’t enough, and my housing isn’t enough so I can’t apply for other people.”

The mother of five arrived to Canada under refugee status in 2001, in hopes of having a better life for herself. She said though she did receive some counselling, years of being in an abusive relationship continues to impact her in many ways.

“I came here and I thought I could better myself, but everyday, I struggle, it’s so hard for me,” she said. “Sometimes I have to make a decision to put food on my table or pay my rent, I was in that situation many times.”

Abdi is also currently enrolled in a one-year business management program, and works part-time doing maintenance and housekeeping. At times she is forced to cut back on her hours, because she has to stay home with the kids when they are doing remote learning.

During an emotional interview, her kids are often times running in the room, wanting to be close to their mother.

She said she keeps this fight up for them, so that they can have a better life. But she wanted to share her story because she needs help, and wants our policies to do a better job at helping victims and survivors of violence.

“They need to understand people are really struggling, there’s a lot of people who need help and they can’t get the help that they need,” Abdi said. “They make rules that if you don’t fit into a category, then you’re not qualified. That shouldn’t be happening.”